Building a Solver for The Witness

0. Inspiration

In case you haven’t heard about it, The Witness is an excellent video game. You basically wander alone on a dreamy island and try to solve the puzzles littered around; it’s like Professor Layton, but with all the NPCs turned into stones. On top of being a great puzzle/exploration hybrid, The Witness is able to teach its players without any word and exposition. I bought it on day one, and it’s well worth it’s full price.

All the puzzles in The Witness take the form of path-searching on a rectangular maze. By drawing a path from start to finish, you complete the puzzle by satisfying specific rules. These rules can roughly be divided into 2 groups: symbolic and environmental. The former comes with symbols on the maze to satisfy (e.g., a black hexagon has to be traversed by the path), while the latter hides its rules and clues in the environment (e.g., the path is indicated by the reflection of sunshine).

It’s a joy to figure out the rules of both, but after a while I found myself looking forward to environmental puzzles more than the symbolic ones. A lot of these symbolic puzzles, ranging from simple path-finding to complex segmentation problems, can be solved with brute-force approaches. As I sat there cutting up small Tetris pieces to figure out a particular torturous Tetris-fitting puzzle, I wonder if this process can be automated.

This was when I decided to build a solver to handle some of these puzzles for me. The preliminary version is complete, and you can try it here.

The following sections will detail some of the design process, as well as some interesting observations I had when working on it. If you want to check out the (messy) codes, click here.

Finally, this project is still work in progress. As more types of puzzle elements are supported, this article will be expanded accordingly.

1. Terminology

Since The Witness is entirely text-free, I have to come up with names for various elements of the puzzle. Skip this part if you don’t feel like reading encyclopedia.

The body of the puzzle is a node map. The node map consists of all the paths and their intersections. The intersection is a node, while the short path between 2 nodes is a side. (BTW, the correct terms for them in graph theory are vertices and edges).

On top of the node map, there’s also a block map. These are just for storing the special blocks between nodes and sides, and it’s completely empty if we’re just dealing with a simple maze. (It’s possible to merge node map & block map into a single matrix, but I decide to keep them separated for simplicity’s sake.)

Heads and tails are the start and end of a puzzle. Judging from the game, tails can only be placed on the border, while there’s no restriction for heads.

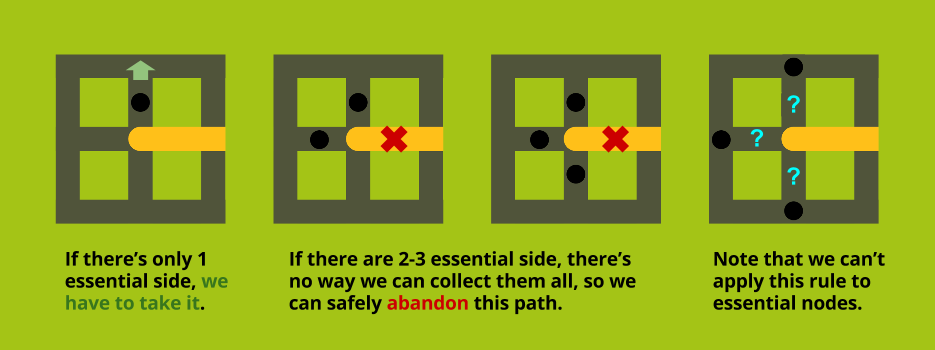

Essential nodes and essential sides are represented by black hexagons, which need to be traversed exactly once with the solution path.

Black/white blocks have to be in different segments. A segment is formed by the solution path, and has to touch the border at least on one side.

(This part will be expanded when more types of elements are supported in the solver)

2. Algorithm & Strategy

Ok, now that we have all the names available, we can delve into the algorithm.

Finding exits & self-validation

If it’s just a simple maze with no essential/blocks/whatever, we can use any path-finding algorithm to solve it. I pick the basic A* algorithm, with G = length of current path & H = Manhattan distance from current node to the tail. Pretty standard stuff.

If there ARE additional puzzle elements, we can iterate through every possible path; for each path, we validate if all the rules have been fulfilled.

But this is suuuuuuuuuuuuper slow

Obviously, it doesn’t make sense to make a beeline for the exit, when we haven’t collected all the essential nodes, or when the exit is blocked off.

One simple improvement is to modify the heuristic of A*. Take essential nodes/sides as an example: Instead of computing the distance between current node and the tail, we look for the closest unvisited essential node/side, and compute the distance to that. Once we reach an essential node/side, G is set to 0, and H is the distance to the next closest essential node/side, and so on so forth.

This heuristic works great when there’re only a few essential elements in the puzzle, but the running time will skyrocket as the puzzle gets bigger. This is understadable, as finding a traceable path is an NP-Complete problem. Don’t expect too much from naive heuristics like the above.

You follow or you die

Essential sides are easier to deal with than nodes, due to a convenient characteristic we can exploit:

Segmentation before it’s too late

Another intuitive thing to do is to constantly check if there’re out-of-reach essential nodes.sides. If we form a segment with the current path, and the segment contains essential elements but no exits, then there’s no point expanding this path at all.

This is an efficient pruning step for every type of puzzle elements. Whenever a path forms a segment around the border, we’ll extract the segment and check if all the elements inside satisfy the rules.

Black/white separation

Black & white blocks are fairly straightforward to evaluate in a segment: we simply count the number of black & white blocks, see if a segment contains both.

Also, if there are black & white blocks next to each other, then the path has to pass through them. It’s like getting a free essential side for every black/white close pair.

3. User Interface

As I fleshed out the underlying solver (it was written in C++ first), I was frustrated by the fact that there’s no user interface for this tool. Eventually I decided to port everything to Javascript, and built a GUI in the form of a website. Since I had next to zero knowledge on HTML/CSS at first, it took me a while to get everything look right.

(One minor thing to point out is that essential nodes/sides are hexagons in the game, but since drawing a hexagon is not trivial with CSS, I replace it with a small dot.)

Once the GUI is done, I restarted the game and ran a couple of the early puzzles through the solver. There’s something satisfying about playing the game this way: building a solver is just as challenging and fun as solving these puzzles yourself.